Greasing The Skids

In this 6-week change management series, TLI staff examine the big ideas and often-overlooked strategies for successfully leading school change. Catch the series introduction or earlier blogs here.

Successful building-level shifts require more than a strong leader. A new curriculum is worthless without the teachers to skillfully integrate it into class. A new technology initiative won’t make it past the storage closet without the people to weave it into courses.

Too often, the human side of change is treated as an afterthought or given a one-size-fits-all approach. After all, it’s hard to help staff navigate the emotion, time pressures, and skill building that change often brings. It’s hard to thoughtfully engage with skeptical faculty and listen carefully to painful criticism.

Regardless of difficulty, planning for how you’ll guide faculty and staff through a big change is a crucial component of successful change. In this blog, we offer a concrete, time-tested strategy to keep people at the center of your change process.

Grease the Skids, a strategy employed by many successful principals with whom we work, is designed to make change run more smoothly. This strategy takes its name from the pallets that easily slide across a factory floor with a little lubrication. We hope it helps eases the burden of change in your school, too.

To Grease the Skids of major change, school leaders start by identifying highly-influential people who aren’t on board with a new initiative. The key is to identify the teachers or school staff members who can quickly influence the people that are on the fence or on the bus (see our earlier post to identify those two groups).

Pilot the Plan

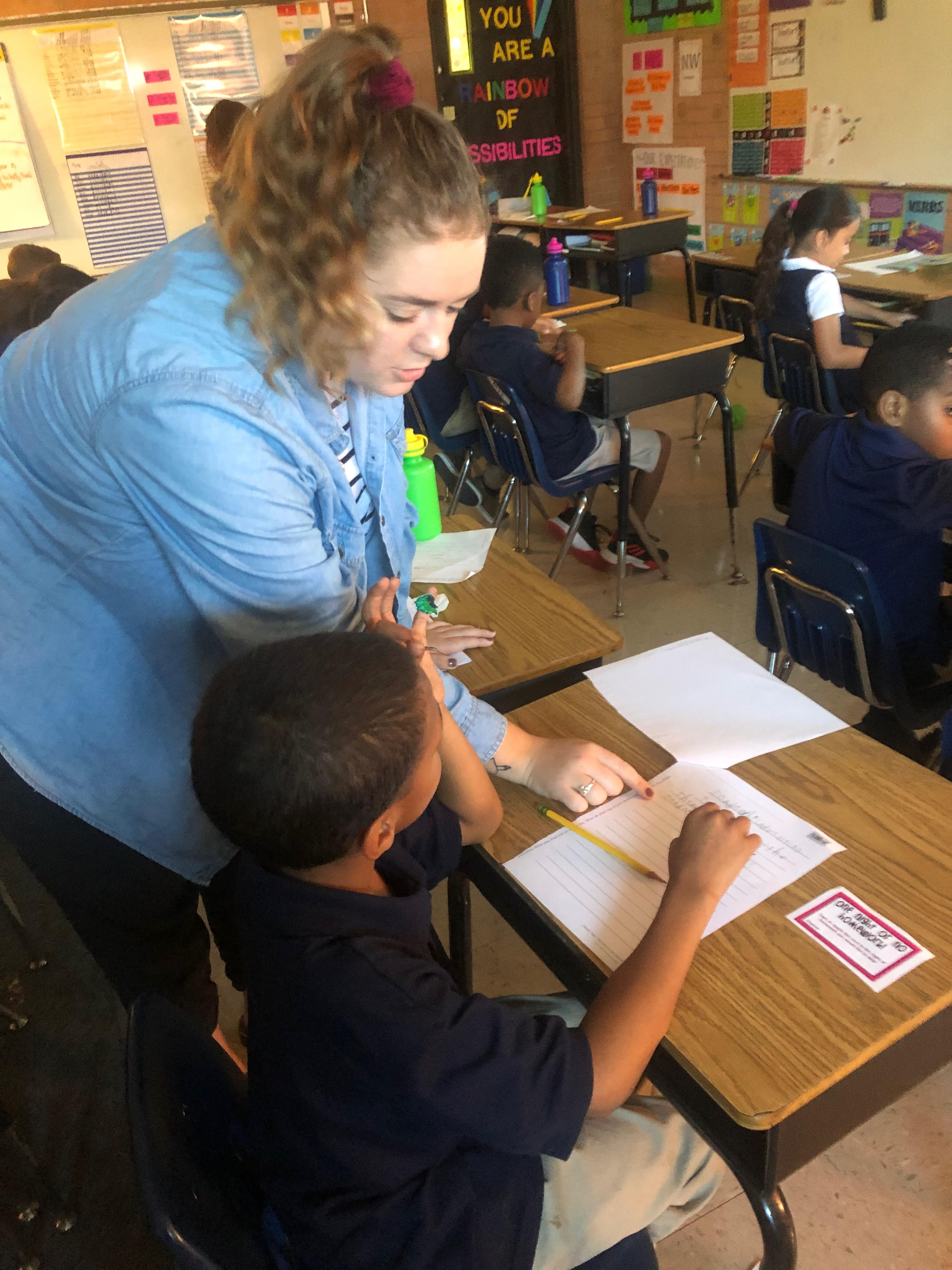

The most popular version of Greasing the Skids is to pilot a new program or initiative with select teachers. Instead of rolling out one-to-one laptops to an entire school, test the idea of a laptop cart with one teacher or a highly-influential grade-level team. The small scale allows leaders to check in regularly, encourage growth, and adjust the plan as needed. It also builds relationships with influential staff members so leaders can eventually rely on these staff members to influence others.

After testing a change with a small group, ask pilot teachers to prepare a testimonial, share data, or offer illustrations on how the change worked. The teachers who used the laptop cart can quickly offer guidance to the full staff on how to build their own tech skills or give examples of how much the laptops helped with the writing process. Not only did you work out the kinks with a small group, but you’ve probably expedited the staff’s buy-in by leveraging influential teachers.

Test the Message

Greasing the Skids can also be a way to test your message with an influential staff member before speaking to the entire faculty. Instead of announcing a new guided reading effort to everyone at once, seek out a few influential teachers for an advance check-in. Explain the rationale and ask for feedback about your approach. Are you taking on the work in the right way? What’s exciting or concerning for the teacher?

By testing the message, school leaders hear important criticism about the change itself and the messaging. If a teacher offers skepticism about the new guided reading initiative being just another under-resourced, under-funded change, the leader can immediately brainstorm how to make sure teachers are well-supported this time. Suddenly, the new teacher is an ally in solving a problem and helping the leader avoid dangerous potholes.

One superintendent we work with teaches his principals to test the message with at least two people before each major announcement or meeting.

Whether you’re launching a change or training faculty on new skills, try to Grease the Skids before you take a change to your whole school.